Darwin's Few

WWII Flying Ace George Preddy Jr & the 49th Fighter Group USAAF during the defence of Darwin in 1942

By Susan Ward ©

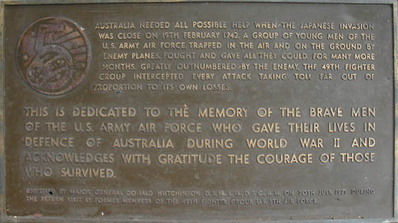

Many people with an interest in WWII aviation know of Major George E. Preddy’s exploits with the 8th Air Force in Europe which has seen him famously fêted by the late Vice Chief of Staff of the USAF, General John C. Meyer as “The greatest fighter pilot who ever squinted through a gun sight.” George's skills as a fighter pilot were honed during during his time in the south west Pacific, flying P-40s in the defence of Australia. Based in Darwin, North western Australia After the first raid on Darwin in February 1942, it was the inexperienced young pilots of the the 49th fighter group who defended Australia's northern coastline against the seemingly invincible Japanese forces.

What were the circumstances in Australia that took Preddy to Darwin with the 49th Fighter Group half a world away? What was life like for him and his compatriots on that wild frontier? It is fortunate that George was a diarist and his daily musings have been preserved, not only giving details of his daily life but also bringing a personal perspective to the political events and preparations for the unfolding world war.

George Preddy grew up in leafy Greensboro North Carolina. He was smitten with a love for flying after his first “real airplane ride” in 1938 when he flew to Danville in a ’33 Aeronca with his friend Hal Foster. George recorded in his daily journal that “I must learn to fly” and pursued his love of flying ardently. In the late thirties as the Second Sino-Japanese war continued to rage on the other side of the planet he was learning to fly. In 1939 George became a barnstormer pilot flying a Waco, learning all the tricks of the trade in stunt work and aerobatics. It came to him easily as he was a talented natural athlete with excellent spatial awareness. As George took to the skies the world was beginning to realise the danger of Nazism which had taken root and was beginning to threaten Europe. Poland was invaded on September 1st 1939. In response Great Britain, France and the British Commonwealth countries of Australia, New Zealand and Canada all declared war on Germany on the 3rd September. A conservative government was in power in Australia and the Prime Minister Robert “Pig Iron Bob” Menzies made the announcement to Australia thus:

“Fellow Australians, it is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence (sic) by Germany and her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.”

Despite the initial neutrality of the United States, George decided he wanted to fly with the military. Joe Noah says in his biography of Preddy, “Wings God Gave My Soul” that the desire to fly bigger more powerful planes was what inspired George, “he wanted more speed, more altitude, more excitement” He flew for the thrill of it.

|

Described by those who knew him as “aggressive, tenacious and eager”, George applied to and was accepted by the USAAF in 1940 after being rejected from the US Navy three times on physical grounds. He spent some time with the Army National Guard, serving with the 252nd Coast Artillery whilst awaiting orders to report for flight training. When he heard of imminent plans to ship the 252nd out to Costa Rica, George applied for transfers about which he heard nothing until on the day his outfit were due to leave. At the eleventh hour George’s commanding officer arranged for an internal transfer.

|

In April 1941 as two thousand American troops were dispatched to the Philllippines and Japan signed a pact of neutrality with the USSR, George’s orders finally came through. No.452 Squadron, the first RAAF unit to be formed under the Empire Air Training Scheme was getting underway in England and Rommel was preparing to cut a swathe through North Africa as George tried his hand at flying a Stearman PT-17. Three months later he moved on to the Vultee BT-15 and George’s confidence grew along with his skill. He was keen to get into pursuit rather than bomber or observation flying and found his understanding of aerobatics very helpful. He finished basic training in October ‘41 and a delighted George moved on to Craig Field in Alabama for advanced pursuit pilot training with the AT-6 Texan. He also tried out a Curtiss P-36 during gunnery training at Elgin Field in Florida, glimpsing the power and speed that was to come with the P-40 in the months ahead defending Darwin.

The capital of the Northern Territory, Darwin is on the north westerly tip of Australia and was strategically situated for maintaining a supply route and transit base for armed forces heading into the Pacific Theatre. The new Australian Prime Minister John Curtin and President Roosevelt had agreed that a combined Australian/American force was the only hope to halt the steady southward movement of the Japanese. Curtin said at the time “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.” When war broke out in the south west Pacific the majority of the Royal Australian Air Force were in Europe and North Africa. In 1939 when Australia had automatically gone to war in defence of King and country, the RAAF had been consigned to Britain. The RAAF prepared Australian flyers for the Royal Air Force and then shipped them off to fight for the Empire. This not only left the shores of Australia undefended but meant that as the Japanese encroached on other nations in the region there was initially no concerted force to hold them back.

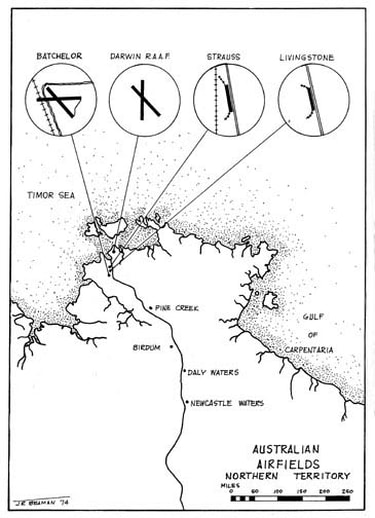

Appreciating the dire situation, the alliance had been formed and a programme undertaken by Australia and the USA to send P-40E Warhawks (known as Kittyhawks to the RAAF) and fighting men to the south west Pacific from the east coast of Australia, dispatching reinforcements to Java and the surrounding area via Darwin. US Far Eastern Air Force Commander General Lewis Brereton had travelled to Australia from the Philippines in mid 1941 to discuss the creation of an aerial supply route to support forces in the Philippines against probable Japanese hostility. With RAAF cooperation a secret network of airfields and supply bases was created which by November of that year became known as the Brereton Route. The route would enable fighter groups such as the 49th to leapfrog across the country, ultimately arriving at one of several bases constructed in and around Darwin.

The capital of the Northern Territory, Darwin is on the north westerly tip of Australia and was strategically situated for maintaining a supply route and transit base for armed forces heading into the Pacific Theatre. The new Australian Prime Minister John Curtin and President Roosevelt had agreed that a combined Australian/American force was the only hope to halt the steady southward movement of the Japanese. Curtin said at the time “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.” When war broke out in the south west Pacific the majority of the Royal Australian Air Force were in Europe and North Africa. In 1939 when Australia had automatically gone to war in defence of King and country, the RAAF had been consigned to Britain. The RAAF prepared Australian flyers for the Royal Air Force and then shipped them off to fight for the Empire. This not only left the shores of Australia undefended but meant that as the Japanese encroached on other nations in the region there was initially no concerted force to hold them back.

Appreciating the dire situation, the alliance had been formed and a programme undertaken by Australia and the USA to send P-40E Warhawks (known as Kittyhawks to the RAAF) and fighting men to the south west Pacific from the east coast of Australia, dispatching reinforcements to Java and the surrounding area via Darwin. US Far Eastern Air Force Commander General Lewis Brereton had travelled to Australia from the Philippines in mid 1941 to discuss the creation of an aerial supply route to support forces in the Philippines against probable Japanese hostility. With RAAF cooperation a secret network of airfields and supply bases was created which by November of that year became known as the Brereton Route. The route would enable fighter groups such as the 49th to leapfrog across the country, ultimately arriving at one of several bases constructed in and around Darwin.

|

On the 7th December 1941 Pearl Harbour was attacked. Japan declared on the 8th of December that European domination had ended in Asia as they landed in Malaya with the intention of vanquishing the British Empire forces within Malaya and Singapore. The Australian War Cabinet minutes for that day state: “Note was taken of the following Admiralty message dated 8 December: Commence hostilities against Japan, repetition, Japan at once.” Governor General Lord Gowrie and PM John Curtin signed the Proclamation of War with Japan the same day. At this time American forces had already begun steadily arriving in Australia under the command of General Douglas Macarthur. George graduated on December 12, 1941. 2nd Lt. George Preddy Jr. had earned his wings, destined to fly P-40 Warhawks with the 9th Pursuit Squadron of the 49th Fighter Group in Darwin.

|

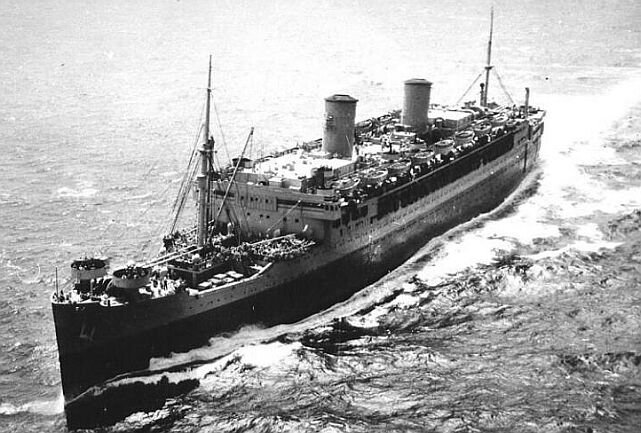

On the 16th December 1941 in Australia, an edict was issued via Darwin’s Newspaper “The Northern Standard” ordering evacuation from Darwin, stating: “Citizens of Darwin, the Federal War Cabinet has decided that women and children must be compulsorily evacuated from Darwin as soon as possible, except women required for essential service.” At this time two thousand of the four thousand residents of Darwin departed, soon to be replaced by incoming Allied armed forces. Almost a month later George set sail on a refitted former luxury liner to an “unknown destination…”

|

January 12th 1942 - Monday

“Left San Francisco Harbour on the Mariposa for unknown destination possibly Australia. About 4,000 men aboard. Ship is armed with 50 calibre anti-aircraft machine guns and 3 inch guns. Also loaded with bombs and P-40s. No radios or cameras can be used, blackout is in effect." On board the USAT Mariposa steaming towards Melbourne the news came through that Rabaul had fallen on the 23rd January and by January 30th Ambon Island had been lost to the encroaching Japanese. By the 31st of January the British forces had entirely withdrawn to Singapore. |

The Mariposa arrived in Melbourne on Monday February 2nd 1942. The 49th set up their billet at Camp Darley about 30 miles from Melbourne, near Bacchus Marsh, appropriately named, as according to his diary George “picked up a girl” the same evening. George was undeniably a ladies' man and never short of company, he and his handsome friends in their smart uniforms and fighter pilot aura of daring and danger had their pick of the local beauties, one called Edna. George celebrated his 23rd birthday on February 5th by getting hammered with friends McGee and Smitty and some local girls. He mentions his other great passion in the same diary entry when he says “ I would surely love to move now and start flying.” Edna wanted him to meet up with her on Valentine´s Day but he wouldn´t risk it as they were due to head off to Brisbane the next day to pick up some p-40s.

Realising the difficulty of invading a continent as vast as Australia the Japanese had formulated a plan whereby they would isolate Australia by occupying various island groups such as Fiji, the New Hebrides, Samoa and the Solomon Islands. By controlling this part of the Pacific, Japan could disrupt American forces trying to get to Australia as well as the severing supply routes. The Japanese also had their eye on the rubber plantations, mineral wealth and oil reserves of the Dutch East Indies. P-40s had already begun being transferred to the Java campaign via the top end but there were still very few military aircraft permanently based at Darwin in February 1942.

At this time Wirraways were the RAAF front line fighter. There were several “weary” Wirraways and a few Lockheed Hudson Bombers stationed at the RAAF Aerodrome. With no fighters to provide cover for the Hudsons losses had been very heavy. The three squadrons of the 49th FG that would be in Darwin by March were still training in the south. According to a contemporary report by General Brett USAFIA an “excessive and alarming” number of accidents during this period occurred which were almost entirely caused by pilot error as a result of little or no experience flying the P-40Es. Brett insisted “Better trainee pilots must be assigned to this theatre.” They actually had plenty of keen talented men but insufficient training aircraft. Although there were no major injuries to the pilots the loss of aircraft due to inexperience was extensive and weakened the force considerably.

Realising the difficulty of invading a continent as vast as Australia the Japanese had formulated a plan whereby they would isolate Australia by occupying various island groups such as Fiji, the New Hebrides, Samoa and the Solomon Islands. By controlling this part of the Pacific, Japan could disrupt American forces trying to get to Australia as well as the severing supply routes. The Japanese also had their eye on the rubber plantations, mineral wealth and oil reserves of the Dutch East Indies. P-40s had already begun being transferred to the Java campaign via the top end but there were still very few military aircraft permanently based at Darwin in February 1942.

At this time Wirraways were the RAAF front line fighter. There were several “weary” Wirraways and a few Lockheed Hudson Bombers stationed at the RAAF Aerodrome. With no fighters to provide cover for the Hudsons losses had been very heavy. The three squadrons of the 49th FG that would be in Darwin by March were still training in the south. According to a contemporary report by General Brett USAFIA an “excessive and alarming” number of accidents during this period occurred which were almost entirely caused by pilot error as a result of little or no experience flying the P-40Es. Brett insisted “Better trainee pilots must be assigned to this theatre.” They actually had plenty of keen talented men but insufficient training aircraft. Although there were no major injuries to the pilots the loss of aircraft due to inexperience was extensive and weakened the force considerably.

|

Singapore was surrendered to the Japanese on February 15th by General Percival. Some 140,000 people were taken prisoner, including about 15,000 Australians. RAAF Spitfire pilot, Flight Lieutenant Edward “Ted” Sly still remembers the general feeling of helplessness amongst the Australians “I was in the United Kingdom…with the fall of Singapore, Australia could be next in the firing line and I was 13,000 miles from home!” In Melbourne, two Wirraways had finally been provided to train the fifty officers in George’s outfit. The first chance George had had to even sit in a ‘plane was February 16th only three days before the first Darwin raids. The attacks on Darwin seemed to take everyone by surprise and suddenly make the threat of invasion real.

|

First Darwin Raid

On the morning of February 19, 1942 just to the north of Darwin on Bathurst Island, Father John McGrath was alerted by local islanders of a large force of aircraft heading towards Darwin. A volunteer with the Royal Australian Navy coast-watching scheme, he radioed in on the top secret frequency “X” or 6840 KHz, the frequency which all Coast Watcher’s radios were crystal locked onto.

The Australian Navy never listened to frequency X. Father McGrath’s message was received in Darwin by Lou Curnock at the Coastal Radio Station VID at 0935 hrs. Curnock then contacted RAAF Operations. In a turn of events remarkably similar to what had transpired at Pearl Harbour only two months earlier, the RAAF incorrectly assumed that the approaching Japanese aircraft were P-40s of the 33rd Pursuit Squadron USAAF. The P-40s were returning to Darwin after bad weather had forced them abort their flight to Timor en route to Java. Realising that no alarm had been raised by the RAAF Curnock called the Office of Naval Intelligence and spoke with Lt. Cdr. J C B McManus as the bombs began falling.

Eyewitness, Gunner Jack Mulholland said “the enemy planes looked like a neat cemetery advancing across a blue field.” The attack was so unexpected that at one of the “ack-ack” stations the predictor crew were actually training on the first flight of approaching Japanese bombers. One of the gunners looking through the telescope yelled “Hell! They’ve got red spots on their wings!”

The attack on Darwin was executed by the same force that had visited destruction on Pearl Harbour. From the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, commanded by Admiral Chuichi Nagumo came 188 aircraft including 71 D3A “Val” dive bombers, 81 B5N “Kate” high level bombers and 36 escorting A6M2 “Zero” fighters in the morning raid. Flying from newly acquired land bases at Kendari in the Celebes and Ambon, for the noon raid the Japanese launched a force of 27 G4M1 “Betty” and 27 G3M1 “Nell” twin engine bombers from the 1st and Kanoya Kus of the 22nd Koku Sentai.

On the morning of February 19, 1942 just to the north of Darwin on Bathurst Island, Father John McGrath was alerted by local islanders of a large force of aircraft heading towards Darwin. A volunteer with the Royal Australian Navy coast-watching scheme, he radioed in on the top secret frequency “X” or 6840 KHz, the frequency which all Coast Watcher’s radios were crystal locked onto.

The Australian Navy never listened to frequency X. Father McGrath’s message was received in Darwin by Lou Curnock at the Coastal Radio Station VID at 0935 hrs. Curnock then contacted RAAF Operations. In a turn of events remarkably similar to what had transpired at Pearl Harbour only two months earlier, the RAAF incorrectly assumed that the approaching Japanese aircraft were P-40s of the 33rd Pursuit Squadron USAAF. The P-40s were returning to Darwin after bad weather had forced them abort their flight to Timor en route to Java. Realising that no alarm had been raised by the RAAF Curnock called the Office of Naval Intelligence and spoke with Lt. Cdr. J C B McManus as the bombs began falling.

Eyewitness, Gunner Jack Mulholland said “the enemy planes looked like a neat cemetery advancing across a blue field.” The attack was so unexpected that at one of the “ack-ack” stations the predictor crew were actually training on the first flight of approaching Japanese bombers. One of the gunners looking through the telescope yelled “Hell! They’ve got red spots on their wings!”

The attack on Darwin was executed by the same force that had visited destruction on Pearl Harbour. From the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, commanded by Admiral Chuichi Nagumo came 188 aircraft including 71 D3A “Val” dive bombers, 81 B5N “Kate” high level bombers and 36 escorting A6M2 “Zero” fighters in the morning raid. Flying from newly acquired land bases at Kendari in the Celebes and Ambon, for the noon raid the Japanese launched a force of 27 G4M1 “Betty” and 27 G3M1 “Nell” twin engine bombers from the 1st and Kanoya Kus of the 22nd Koku Sentai.

|

Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire from the ships in Darwin Harbour, great damage was inflicted during the two raids that day with 23 ships sunk or badly damaged. This accounted for half the ships in port and the two ships Don Isidro and Florence D which were underway at the time of the attack. The USS Peary was lost with 91 lives, almost half of the official death toll from the raid. The US Navy had been in Darwin preparing to transport troops to support the allied and US forces in Java. Of the 10 P-40Es of the 33rd PS (Provisional) which were returning from the aborted mission to Java, five had been on patrol when the Japanese struck and only one survived the day. In all, 26 aeroplanes were destroyed including 23 allied aircraft.

|

The Post Office which housed the Cable Office, the Police Station and Telegraph Station was completely levelled, killing the postmaster and his entire family. The city was in ruins and all services including the railway line were cut. Mrs Abbott, the Darwin Administrator’s wife said, “When we looked out on our so lovely harbour no picture of an inferno could equal what we saw. Black smoke rolled in heavy clouds; flames rose in great tongues to the sky…the water was covered with black oil. In this water small navy boats were moving, rescuing blackened figures and men were struggling towards our garden where the black water was licking the shore”

There were 252 deaths and 350 people injured or missing. The attacking forces dropped almost 80% of the amount of bombs dropped on Pearl Harbour on the 19th February “using a sledgehammer to crack an egg” as Commander Mitsuo Fuchida reportedly said. Darwin endured 46 raids during the war with a total of 64 in the top end.

George wrote on the 19th, “Flew the Wirraway again today, sure need a lot of practice to get the touch may be leaving here soon because the Japs bombed Darwin today, am anxious to get a crack at them but hope to be familiar with the P-40 first” at this time with the threat of invasion more pressing than ever, practice with the P-40 was still seen as a luxury by those in power.

On the 20th the Japanese invaded Timor. In Australia the Darwin raids were played down in the press. The official death toll for the raid was only 17. A Sydney newspaper ran a photograph on the front page of a huge column of black smoke and the caption, "Large grass fires burning in the Darwin area." The Brisbane Courier Mail stated on Feb 20th that “There were some casualties and some damage was done to service installations.” The fall of Singapore four days previously was still hot news and there was an article on the front page of the same paper sensationalising Japanese atrocities saying that on hospital ships evacuating Singapore “…the decks were continually machine gunned…During the attacks Australian nurses lay on top of children to protect them.” In an attempt to boost morale and stem panic Prime Minister Curtin announced that “Darwin has been bombed but it has not been conquered”. At this time the American flyers were yet to have any training on the combat aircraft they would be flying against the Japanese within the month!

On the 22nd of February George finally got his hands on a P-40. There were only two available and he spent his allocated two hours familiarising himself with the controls and instruments. Two days later he had an hour and a half of flying practice prior to heading off on the long trip to Brisbane to pick up a P-40 and bring it back to Sydney where he put in as much time as he could. He was keen to pick up tips from the more experienced flyers. One of these was Captain Boyd. D. “Buzz” Wagner, one of the first American aces of the war. George noted: “He knows airplanes and tactics inside out. He is certainly no lucky pilot - he’s the real thing! I have a lot of respect for a guy like that."

There were 252 deaths and 350 people injured or missing. The attacking forces dropped almost 80% of the amount of bombs dropped on Pearl Harbour on the 19th February “using a sledgehammer to crack an egg” as Commander Mitsuo Fuchida reportedly said. Darwin endured 46 raids during the war with a total of 64 in the top end.

George wrote on the 19th, “Flew the Wirraway again today, sure need a lot of practice to get the touch may be leaving here soon because the Japs bombed Darwin today, am anxious to get a crack at them but hope to be familiar with the P-40 first” at this time with the threat of invasion more pressing than ever, practice with the P-40 was still seen as a luxury by those in power.

On the 20th the Japanese invaded Timor. In Australia the Darwin raids were played down in the press. The official death toll for the raid was only 17. A Sydney newspaper ran a photograph on the front page of a huge column of black smoke and the caption, "Large grass fires burning in the Darwin area." The Brisbane Courier Mail stated on Feb 20th that “There were some casualties and some damage was done to service installations.” The fall of Singapore four days previously was still hot news and there was an article on the front page of the same paper sensationalising Japanese atrocities saying that on hospital ships evacuating Singapore “…the decks were continually machine gunned…During the attacks Australian nurses lay on top of children to protect them.” In an attempt to boost morale and stem panic Prime Minister Curtin announced that “Darwin has been bombed but it has not been conquered”. At this time the American flyers were yet to have any training on the combat aircraft they would be flying against the Japanese within the month!

On the 22nd of February George finally got his hands on a P-40. There were only two available and he spent his allocated two hours familiarising himself with the controls and instruments. Two days later he had an hour and a half of flying practice prior to heading off on the long trip to Brisbane to pick up a P-40 and bring it back to Sydney where he put in as much time as he could. He was keen to pick up tips from the more experienced flyers. One of these was Captain Boyd. D. “Buzz” Wagner, one of the first American aces of the war. George noted: “He knows airplanes and tactics inside out. He is certainly no lucky pilot - he’s the real thing! I have a lot of respect for a guy like that."

Lt. Preddy joined Lt. Kruzel's Dragon Flight.

Lt. Preddy joined Lt. Kruzel's Dragon Flight.

By late February, thousands of refugees and evacuees from the south west pacific had passed through Broome south of Darwin before heading to the southern capitals. Early on March 3rd Zeros of the 3rd Ku based at Koepang and Penfui airfields on Timor attacked Broome using intelligence from two predawn reconnaissance missions on the 2nd and 3rd. Knowing there would be no resistance, they destroyed every operational aircraft in Broome and killed at least 40 people.

Twenty three Kittyhawks and one B-17 set off towards Brisbane from Bankstown in Sydney on March 7th. Bad weather and low cloud forced the group to return after flying almost three quarters of the way. In early 1942 little more than 1% of Australia had been mapped, this combined with dodgy compasses in the P-40Es made a mother ship necessary for navigation. They finally made the trip on the 10th and spent some time in Brisbane for refitting before heading off across the country via the Brereton Route to Charleville on the 13th and on to Cloncurry on the 14th. After delays in Cloncurry they continued flying over land which George describes as being “so desolate it was scary” arriving in Daly Waters on the 16th. The inexperience of the pilots inevitably took its toll with only thirteen of the original twenty five Kittyhawks arriving in Darwin on the 17th.

Twenty three Kittyhawks and one B-17 set off towards Brisbane from Bankstown in Sydney on March 7th. Bad weather and low cloud forced the group to return after flying almost three quarters of the way. In early 1942 little more than 1% of Australia had been mapped, this combined with dodgy compasses in the P-40Es made a mother ship necessary for navigation. They finally made the trip on the 10th and spent some time in Brisbane for refitting before heading off across the country via the Brereton Route to Charleville on the 13th and on to Cloncurry on the 14th. After delays in Cloncurry they continued flying over land which George describes as being “so desolate it was scary” arriving in Daly Waters on the 16th. The inexperience of the pilots inevitably took its toll with only thirteen of the original twenty five Kittyhawks arriving in Darwin on the 17th.

Following the initial raids Darwin was a ghost town of empty streets, abandoned buildings and silence. When George Preddy and his companions of the 9th Pursuit Squadron arrived in Darwin, Marshall Law was in place and there was a sense of calm expectation. The remaining residents and armed forces had been resolutely awaiting the arrival of aerial defences, aware that the Japanese could land at any time. There was general excitement and a boost to morale when the American Kittyhawks began arriving. Aussie veteran Jack Mulholland said “They looked pretty damn good to us. We saw them as having come down under to save us from the advancing hordes and we were glad to have them with us!"

|

Ready or not, the 9th Squadron arrived in Darwin on 17th March. George wrote in his diary, “Finally got to Darwin with half the ships we started out with…this place really shows the affects of bombing, buildings and hangars are blasted all to pieces and big bomb craters are all over the ground .” Some of the city was still intact as he also wrote “All of the civilians have evacuated the town leaving swell hotels and apartment houses fully furnished. It is swell to get a place with running water, refrigerator and all the conveniences.” They were soon in the thick of it, flying operations from Batchelor field about 50 miles south of Darwin.

The first operational patrol flew out of Batchelor on 19th March 1942 and the young pilots quickly realised that there were fundamental flaws in the operation. There was no decent early warning system as George relates “The alert around Darwin is lousy, we never get the call until bombing has begun, then it is too late.” Flights often took to the sky just in time for an aerial view of the destruction. This, combined with the problems of taking a P-40 rapidly to altitude resulted in a great deal of frustration. The escorting Zeros usually maintained an altitude advantage, knowing that pulling a P-40’s nose up suddenly and firing the guns could result in a stalled aeroplane. |

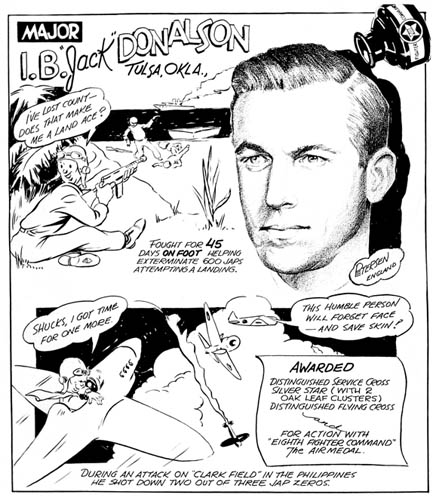

On the 22nd of March George recorded in his diary that “Harvey and Poleschuk shot down a Jap recon ship, the first for our squadron.” 49th FG records show that a Type 97 “Babs” escorted by 3 fighters were tracked on the new radar that just come on line that morning. The Japanese had enjoyed a month of unopposed sorties over Australia but the newly arrived Americans had put an end to that. Although Japanese records indicate no loss for the 22nd March, they quickly realised that a change in tactics was required. Mission planners could no longer send bomber formations over the Darwin area without escorting fighters as they were now at the mercy of an enthusiastic if not particularly experienced group of young fighters. All the flyers were under 24 years of age, most, like Preddy had no combat experience at all. March 22nd also saw the arrival of “three old pilots who have seen action in the Philippines and Java, (Lt. William Irving, Captain Joseph J. Kruzel and Lt. Andrew Jackson Reynolds) it is nice to have someone around who knows...how the Japs operate. When our meeting was held tonight all the squadrons were changed around, forming eight flights.” Until Lt. Jack Donalson arrived in April the three new pilots were the only veterans in the squadron.

The Japanese launched strikes against the RAAF airfield in Darwin on 28th March with seven unescorted bombers arriving only to be sent on their way with one shot down and one damaged. George wrote “the boys at Darwin intercepted (seven Jap Bombers) on the way back to Koepang and knocked down two for sure and possibly disabled two more.” Throughout the history of aerial combat over claiming has been the rule rather than the exception and the skies over Darwin were no different. The Japanese changed tactics and on 30th and 31st March there were Zeros in escort for the first time.” The 9th PS was there to challenge them but the fledgling P-40 pilots were only able to claim one Zero in the subsequent engagements.

On 30th March Lt. Preddy and his mates took off from Batchelor and patrolled for a while before returning to refuel only to be scrambled almost immediately to intercept an incoming attack. They arrived in time to intercept the Bettys but were bounced by Zeros. George says ruefully of the engagement “I had a perfect shot at a Zero, but missed by not turning one gun switch on.” He was to have plenty more practice, as Hollywood producer Lucien Hubbard noted when he visited Humpty Doo in 1942 “The Japs (came) again and again, in Zeros and Bombers. The green kids went up to meet them.”

|

The Japanese came over often on moonlit nights for reconnaissance missions and George noted that he saw “three bombers for the first time at night" on the 31st of March

they returned on April 4th with a force of six Betties and six escorting Zeros and attacked the civil ‘drome at Parap, only two and a half miles from central Darwin. Crews of the Australian 14th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery had their range and altitude dialled in and shot down two of the bombers before the 9th Pursuit Squadron transmitted a “Tally Ho” over the R/T, the pre-arranged signal for the ground gunners to hold their fire. Diving through the Japanese formation, the P-40 pilots claimed two Zeros and six Bettys. |

George relates the day’s events… “We gave the Japs the prettiest surprise today. When they came over with seven bombers and three Zeros at 23,000 feet, we had a flight of seven P-40s at 26,000 waiting for them. When they left there were only two bombers and one Zero. Reynolds is becoming quite an ace, adding a bomber and a zero to his credit. Gardner was hit by our own ack-ack and bailed out. Livingstone overshot a landing on a forced landing after the combat and was killed when his engine cut out.”

|

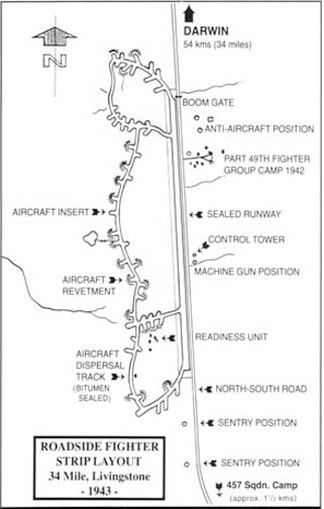

The airfield where Lt. Livingstone crashed was known simply as 34-mile airstrip, (some time later it was renamed Livingstone Field) it was one of four paved air strips in the immediate vicinity of Darwin built alongside the main north-south road between Darwin and Adelaide, over 3,000 kilometres to the south. George and the 9th PS set up digs there on April 14th “We have a camp built and are dispersed in the woods.” By this time George had been assigned to Kruzel’s Flight and said of the change “I believe I will like flying under his command.”

Monsoonal Darwin is oppressively hot, from October until April with cloying humidity and temperatures hovering around 35+ Degrees Celsius in the shade, punctuated by dramatically violent electrical storms. |

The heat is relentless, famously rendering the inhabitants “troppo” during this time of the year. Prickly heat and fungal infections were rife. George said “The mosquitos are so bad you have to crawl in bed under a net after supper to stay in one piece.” The mid year “Dry” replaces the mugginess with cooler, dry, dusty conditions. Despite the difficult conditions the pilots did their best to make themselves comfortable in Australia's northern combat zone. Their camps had volleyball nets, board games and furnishings requisitioned from Darwin buildings, including the Hotel Darwin, in a village of tents shaded by gum trees.

The Japanese attacked Darwin three more times in April, the biggest raid coming on ANZAC Day, the 25th with a force of 27 bombers 15 fighters and one reconnaissance plane despatched against the RAAF airfield on the outskirts of town. This was the first time that all three squadrons of the 49th Fighter Group operated as a unit. The 49th claimed a total of ten bombers and two fighters destroyed and one bomber damaged against no P-40 losses. The Japanese returned two days later and although at the time the 49th claimed victories over three bombers and four fighters, four P-40s were lost. George was thrilled to be getting some combat experience and was pleased to be able to make damaged claims for a Zero and a Type 97 Bomber, though still chafing from the lost opportunity to down his first plane. Three P-40s from the 8th Squadron were destroyed as was one from the 7th Squadron. There is some discrepancy as to actual numbers of enemy attackers during these battles as well as the number of kills and the above scores have been taken from George’s diary entries for the days of the battles. George wrote of the engagement on the 28th … “Captain Strauss and a lieutenant are still missing. Andrew and Martin were both shot down and one jumped while the other made a forced landing in the water. Fish was shot through the head and was last seen going into the bay with his engine wide open and all guns firing.”

April finished on a sad note with a runway collision which claimed the lives of Brigadier General George, war correspondent Melville Jacoby and Lt Jasper of the 9th. Their VIP transport, a Lockheed C-40 Electra had just landed when it was hit by a P-40 whose pilot had been blinded by dust and swerved off the runway on take off . Co-pilot of the Electra, Jack Donalson stayed on with the 9th. George Preddy had a great deal of respect for the General and describes him as “Probably one of the best pursuit pilots and authority in the world.”

The Japanese attacked Darwin three more times in April, the biggest raid coming on ANZAC Day, the 25th with a force of 27 bombers 15 fighters and one reconnaissance plane despatched against the RAAF airfield on the outskirts of town. This was the first time that all three squadrons of the 49th Fighter Group operated as a unit. The 49th claimed a total of ten bombers and two fighters destroyed and one bomber damaged against no P-40 losses. The Japanese returned two days later and although at the time the 49th claimed victories over three bombers and four fighters, four P-40s were lost. George was thrilled to be getting some combat experience and was pleased to be able to make damaged claims for a Zero and a Type 97 Bomber, though still chafing from the lost opportunity to down his first plane. Three P-40s from the 8th Squadron were destroyed as was one from the 7th Squadron. There is some discrepancy as to actual numbers of enemy attackers during these battles as well as the number of kills and the above scores have been taken from George’s diary entries for the days of the battles. George wrote of the engagement on the 28th … “Captain Strauss and a lieutenant are still missing. Andrew and Martin were both shot down and one jumped while the other made a forced landing in the water. Fish was shot through the head and was last seen going into the bay with his engine wide open and all guns firing.”

April finished on a sad note with a runway collision which claimed the lives of Brigadier General George, war correspondent Melville Jacoby and Lt Jasper of the 9th. Their VIP transport, a Lockheed C-40 Electra had just landed when it was hit by a P-40 whose pilot had been blinded by dust and swerved off the runway on take off . Co-pilot of the Electra, Jack Donalson stayed on with the 9th. George Preddy had a great deal of respect for the General and describes him as “Probably one of the best pursuit pilots and authority in the world.”

|

A seven week respite followed after the April raids. During this time George and his squadron mates settled into a routine as they continued to fly patrols out of Livingstone Field at Humpty Doo and perform training missions to hone their skills. By May the humidity was decreasing with the onset of “the dry” giving everyone a much needed break. On 8th May the battle of the Coral Sea took place. Meanwhile, at Humpty Doo they were concentrating on necessities as George wrote “Captain Kruzel and several other pilots went buffalo hunting and shot two large ones and a calf. We will probably be eating buffalo for the next month.” There is no mention of the Coral Sea until the 12th when George says “There has been a lot of talk about the big naval battle off New Guinea where the U.S. sank several Jap warships and troop ships. It is believed that this was directly responsible for stemming an invasion of Australia”. There was also an official announcement by the War Department of Doolittle’s raid.

|

The quiet time they were experiencing was the result of concentrated attacks on Port Moresby in New Guinea and also further south. On 31 May 1942 HMS Kuttabul lost 21 sailors during a raid by Japanese midget K-IX submarines in Sydney. Six Japanese submariners lost their lives. They were discovered to be Kamikaze and were buried at the time respectfully with military honours despite grumblings from the press who were busy with propaganda of their own. (Since the war the ashes have been returned to Japan and the men have posthumously become national heroes.) In June Midget submarines went on to attack inside Sydney Head whilst beachside suburbs were shelled by larger submarines.

The relative peace was shattered on June 13th with an attack on the RAAF airfield in Darwin. The following day 27 Zero fighters strafed the city. On June 15th the Larrakeyah Barracks and Stokes Hill were targeted, “Heavy bombers, about 27 of them, dropped their load on the town at noon. Our flight went into the attack just before they reached their target but we were attacked from above by several Zeros. We were forced to dive out but Manning’s flight caught them from above. After the enemy turned west, Manning and McComsey got one Zero each with Peterson and Fowler getting one between them. Taylor damaged one and the 7th got another. My ship was hit in three places. Otherwise, the squadron received no damage.” As a parting gesture on the 16th 27 bombers escorted by 27 Zeros returned to bomb what was left of Darwin town. There were no more raids that month. The box score for the four day killing spree was more or less even with 11 Japanese fighters claimed destroyed for the loss seven of P-40s with an additional three crash landings.

The relative peace was shattered on June 13th with an attack on the RAAF airfield in Darwin. The following day 27 Zero fighters strafed the city. On June 15th the Larrakeyah Barracks and Stokes Hill were targeted, “Heavy bombers, about 27 of them, dropped their load on the town at noon. Our flight went into the attack just before they reached their target but we were attacked from above by several Zeros. We were forced to dive out but Manning’s flight caught them from above. After the enemy turned west, Manning and McComsey got one Zero each with Peterson and Fowler getting one between them. Taylor damaged one and the 7th got another. My ship was hit in three places. Otherwise, the squadron received no damage.” As a parting gesture on the 16th 27 bombers escorted by 27 Zeros returned to bomb what was left of Darwin town. There were no more raids that month. The box score for the four day killing spree was more or less even with 11 Japanese fighters claimed destroyed for the loss seven of P-40s with an additional three crash landings.

|

For the Americans it was a matter of urgency to log as many hours as possible. They were up against seasoned veterans some of whom had seen years of combat in China. In the absence of enemy activity the pilots were in the air as much as possible. Preddy and his mates were flying the Curtis P-40E Warhawk which was well armed with six 50 calibre Browning machine guns and provided the pilot with ample protective amour. Compared to the nimble A6M2 Zeros that their opponents of the 3rd Kokutai were equipped with, the P-40 was more cumbersome. The Zero could easily out-turn a P-40 so the Americans avoided dog fighting when possible. They preferred to dive through the enemy fighter and bomber formations, lining up on a target, firing a burst or two and then continuing on below the enemy. Once below, the P-40s could use the speed gained in the dive to climb back above the Japanese formation for a second attack.

George had settled into a routine of sorts, dogfighting, attending lectures, censoring mail, having “bull sessions” with the boys with the occasional bottle of whiskey and working with the others to set up camp and make it comfortable. He also did a lot of laundry, which he mentions in his diary with great regularity! Lucien Hubbard describes the “Dewy idealism…of our own “few” who are doing so much for so many…” the Boy Scout camp where “monopoly was played by landless youths who were giving their best years to the acrid business of killing and being killed.” |

The last week of June, General Brett and three other Generals paid a visit to the north. They admitted that decisions made in December of 1941 to send inexperienced pilots into combat had been a mistake. Relieved to have survived this period George felt by now he was “a little better prepared having learned from actual experience how to take care of myself up there, there is something to be learned on each mission and I am just a beginner.” With the Japanese concentrating on territories around New Guinea, the pilots of the 49th continued training in relative peace, they busied themselves doing odd jobs around the camp such as making an oven out of an anthill, building a volleyball court and the general feeling was that owing to the change in direction of the Japanese onslaught away from Darwin their group would be moving on soon. George summed it up in his July 4th diary entry, ”Tojo usually furnishes the target for our fireworks on holidays but he didn’t comply this time.” George was “still sweating out a ride south” hoping to get leave before they moved on, possibly to New Guinea.

|

Late in the afternoon on 12 July two flights of 9th squadron P-40s took off on a training flight over the Manton Dam south of Darwin to practice diving attacks on enemy formations. Preddy was flying on Lt. Richard Taylor’s wing and the two were pretending to be the Japanese targets flying at 12,000 feet. Lt. John Sauber and Lt. I.B. Jack Donalson climbed to 20,000 feet to make mock diving attacks. Sauber flying in No. 87 went first and dove on Preddy’s P-40.

|

Jack Donalson recalled the moment “Sauber...looked at me and signalled he was starting his pass and I could see clearly that he was too close to have room to manoeuvre...before he could break off the pass he collided with Preddy.” He severed the tail from Preddy’s P-40, No. 85, “Tarheel” just behind the cockpit. Preddy was seen to egress his stricken craft but Sauber went down with his ship.

Back at Livingstone Field the crash crews raced against the rapidly setting sun to where Lt. Clay Tice was holding the position of the spot where he had seen Lt. Preddy’s white parachute canopy float into the bush. Approaching the spot where Preddy landed, according to Lucien Hubbard’s rather dramatic version of events he and Bill Irving ran through the bush for about a mile, Hubbard “caught a glimpse of white half way up the ridge, and made for it…it was Preddy. He was lying on his parachute. “Gee, fellow, I am glad to see you!” he called out…”Is my leg bleeding much? Is the artery ok?” He had bandaged it himself from his first aid kit. Falling through trees his body had broken through a big branch, gouging a deep hole in his hip and breaking his leg. He seemed more concerned about a thirty-foot termite mound nearby, not the best place to kip down for the night! When Irving arrived Preddy grinned. “You owe me dough boy,” he said. “I bet I’d be the first to date one of those new nurses down at Adelaide River!"

Back at Livingstone Field the crash crews raced against the rapidly setting sun to where Lt. Clay Tice was holding the position of the spot where he had seen Lt. Preddy’s white parachute canopy float into the bush. Approaching the spot where Preddy landed, according to Lucien Hubbard’s rather dramatic version of events he and Bill Irving ran through the bush for about a mile, Hubbard “caught a glimpse of white half way up the ridge, and made for it…it was Preddy. He was lying on his parachute. “Gee, fellow, I am glad to see you!” he called out…”Is my leg bleeding much? Is the artery ok?” He had bandaged it himself from his first aid kit. Falling through trees his body had broken through a big branch, gouging a deep hole in his hip and breaking his leg. He seemed more concerned about a thirty-foot termite mound nearby, not the best place to kip down for the night! When Irving arrived Preddy grinned. “You owe me dough boy,” he said. “I bet I’d be the first to date one of those new nurses down at Adelaide River!"

|

With nothing to do but lie around in bed waiting to be shipped out to hospital, George updated his diary regularly, the day after the crash feeling rather sore and sorry for himself he recounts the fateful incident ”…just lying in bed cut all up and stiff as a board. At least, I am thankful to be here at all. Sure sorry about Sauber. My right hip is cut about off and there is a big gouge in my left calf. Also my right shoulder is cut up. Sure lucky!”

Shipped off to Melbourne via Alice Springs to recover, George found himself in a bed near Major Robert Van Auken who was recovering from burns received when baling out over Melville Island during the raid on 13th June. He had been rescued by an Aboriginal known as “Old Johnny” and canoed back to Darwin for treatment. George and Van Auken had come down from Darwin in the same group. George recounts his first meeting with Joan Jackson, the girl he would later get engaged to. ”Major Van Auken has been blessed with two beautiful female visitors today…” Thereafter they visited often, bringing books and treats. |

George kept abreast of the happenings of the war from his hospital bed. He was jubilant that a new early warning system had finally been created and the now seasoned combat pilots were setting upon the Japanese invaders with alacrity and sustaining fewer losses than ever. George’s diary entry for August 25th says” The Russians are sure catching hell around Stalingrad …News came today that Japs raided Darwin Sunday with 27 Bombers and 20 Zeros. We got 9 Zeros and 4 Bombers without a loss. They can come every day if our boys can knock them down like that!” George mentions in the same entry that his mate Jack Donalson had been awarded the DSC for service in Bataan. During his stay in hospital George was interviewed by ABC Radio, his interview was transmitted back to the States on August 30th.

|

George dated various girls during his convalescence and resumed his friendship with Edna but he was falling in love with Joan and describes her as “…what I have been looking for, beautiful, smart, nice family and good fun to be with.” Before long Joan was wearing George’s wings. They spent plenty of time together and particularly enjoyed visiting Luna Park at St Kilda, going dancing and riding the rollercoaster. From their first meeting on the 23rd July until George departed three months later the two became increasingly close as his diary reflects. “Had dinner at Joan’s house …it was a very enjoyable evening...I think I could love Joan.” George was a regular guest at the Jackson's home and was included in many of their social and sporting activities during his convalescence, including playing golf with Joan's dad. Gus Jackson was a well known golf champion.

When Joan waved George off on the Brisbane train on the 20th October 1942 she couldn’t know she would never see him again. George wrote “I just realized how much Joan cares for me and means to me after seeing how hard she took my departure.” A short while later he asked her to marry him. |

Arriving in Brisbane George expected to head on to New Guinea. Instead he was greeted with “two sets of orders within one hour, one set promoting me to first lieutenant and the other sending me home.” He departed Amberly Field for home in a B-24 on October 23, 1942.

Leaving the 49th behind to continue the push in New Guinea without him, George headed back to the USA, where after some leave and time to see his family and have some southern fried chicken, he returned to service, continuing his training until he was called to the First Air Force on the 30th December 1942. On December 31st George reflected on the past year, “Well here it is, the last day of 1942, a year I will not soon forget. I am on a train setting out on my sixth crossing of the country since this time a year ago. Trips twice across the Pacific Ocean and up and down the continent of Australia have given me some great experiences. Hope by the end of next year I can have done more for my country than I have this year.”

Although George did not score any personal victories over the Japanese while defending Australia he had learned many valuable lessons. He had looked in the face of death as well as love. George Preddy has been described by contemporaries as having “A core of steel in a largely sentimental soul.” In a war that was all about the business of “killing and being killed”, the experiences of the young George Preddy, his account of the situation in Australia and the daily details he shares reveal an intelligent and thoughtful man who would indeed take the experience of combat to a new level when he entered the European Theatre in 1943.

During WWII Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s WWI score of 26 enemy aircraft destroyed became the benchmark of the exceptional American fighter pilot. History shows that although he did not survive the war George went on to be one of the few legendary aces that equalled or surpassed that total and became the top scoring P-51 Mustang ace of all time. The Greensboro Daily News would say of George “His aim was deadly, his flying skill remarkable."

All Photos and images are © Stardust Studios, Bob Alford and 352nd FG Association, and may not be used without permission.

Copyright © 2007 by Stardust Studios. All rights reserved

Leaving the 49th behind to continue the push in New Guinea without him, George headed back to the USA, where after some leave and time to see his family and have some southern fried chicken, he returned to service, continuing his training until he was called to the First Air Force on the 30th December 1942. On December 31st George reflected on the past year, “Well here it is, the last day of 1942, a year I will not soon forget. I am on a train setting out on my sixth crossing of the country since this time a year ago. Trips twice across the Pacific Ocean and up and down the continent of Australia have given me some great experiences. Hope by the end of next year I can have done more for my country than I have this year.”

Although George did not score any personal victories over the Japanese while defending Australia he had learned many valuable lessons. He had looked in the face of death as well as love. George Preddy has been described by contemporaries as having “A core of steel in a largely sentimental soul.” In a war that was all about the business of “killing and being killed”, the experiences of the young George Preddy, his account of the situation in Australia and the daily details he shares reveal an intelligent and thoughtful man who would indeed take the experience of combat to a new level when he entered the European Theatre in 1943.

During WWII Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s WWI score of 26 enemy aircraft destroyed became the benchmark of the exceptional American fighter pilot. History shows that although he did not survive the war George went on to be one of the few legendary aces that equalled or surpassed that total and became the top scoring P-51 Mustang ace of all time. The Greensboro Daily News would say of George “His aim was deadly, his flying skill remarkable."

All Photos and images are © Stardust Studios, Bob Alford and 352nd FG Association, and may not be used without permission.

Copyright © 2007 by Stardust Studios. All rights reserved